| Click here to enter the art museum. |

"Waterfall" can be described as a perpetual motion machine or as a primitive solution to our modern energy crises. The lithograph illustrates a watermill that supplies continuous power, without recourse to the hydrologic cycle.

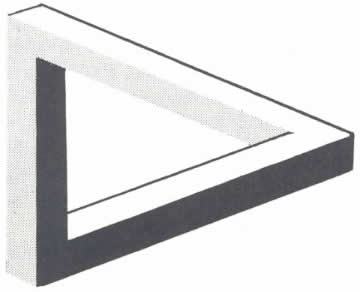

M.C. Escher's print illustrates the "impossible triangle" (see illustration 1) described by the British mathematician Roger Penrose in a 1958 article on visual illusion: "Here is a perspective drawing, each part of which is accepted as representing a three-dimensional, rectangular structure. The lines of the drawing are, however, connected in such a manner as to reproduce an impossibility. As the eye pursues the lines of the figure, sudden changes in the interpretation of the distance of the object from the observer are necessary."

Illustration 1. The "Impossible Triangle"

The impossible triangle is fitted three times over into "Waterfall." Falling water keeps a waterwheel in motion and subsequently flows along a sloping channel between two towers, zigzagging down to the point where the waterfall begins again. The miller simply needs to add a bucketful of water from time to time, in order to compensate for loss through evaporation. The two towers are the same height and yet the one on the right is a storey lower than the one on the left.

Maurits Cornelis (better known as M.C.) Escher, born in Leeuwarden, Netherlands, 17 June 1898, received his first instruction in drawing at the secondary school. From 1919 to 1922, he attended the School of Architecture and Ornamental Design in Haarlem where he studied graphic arts. In 1922 he went to Italy and 1924 settled in Rome. During his 10 year stay in Italy he made many tours, visiting Abruzzia, the Amalfi coast, Calabria, Sicily, Corsica, and Spain. In 1934, he left Italy, spent 2 years in Switzerland and five years in Brussels before settling in Baarn (Netherlands) in 1941, where he died on March 27, 1972.

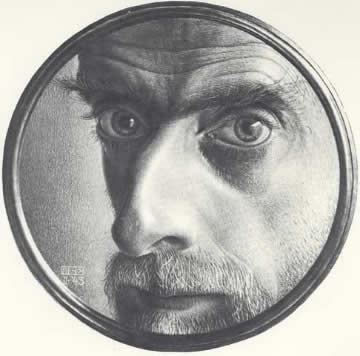

M.C. Escher was one of the world's most original artists (see Illustration 2); his technical mastery is unmistakable. The fact that his imagination was eccentric cannot be denied; Escher's work is at once surrealistic, representation, and macabre.

Illustration 2. E.C. Escher Self Protrait (1943)

Source: M.C. Escher, 1971, The Graphic Work of M.C. Escher, Ballantine Books.